Overview

An extensive study of earthing grids using SafeGrid Earthing Software designed for determining the performance of grids of arbitrary geometrical configuration in two-layer soils has been undertaken. The study confirms work by Dawalibi and Mukhedkar undertaken using software called CDEGS.

A variety of earth grid configurations and soil models were analysed. Important physical parameters have been varied and results pertaining to safety have been calculated; including ground resistances, ground potential rise, and touch, and step potentials.

The results of this study aim to prove the following:

- Simplified methods of analysis such as the equations presented in IEEE Std. 80 make too many assumptions and fail to accurately predict performance of earthing systems.

- The results obtained agree with the physical theory and match closely with results from other similar research and studies.

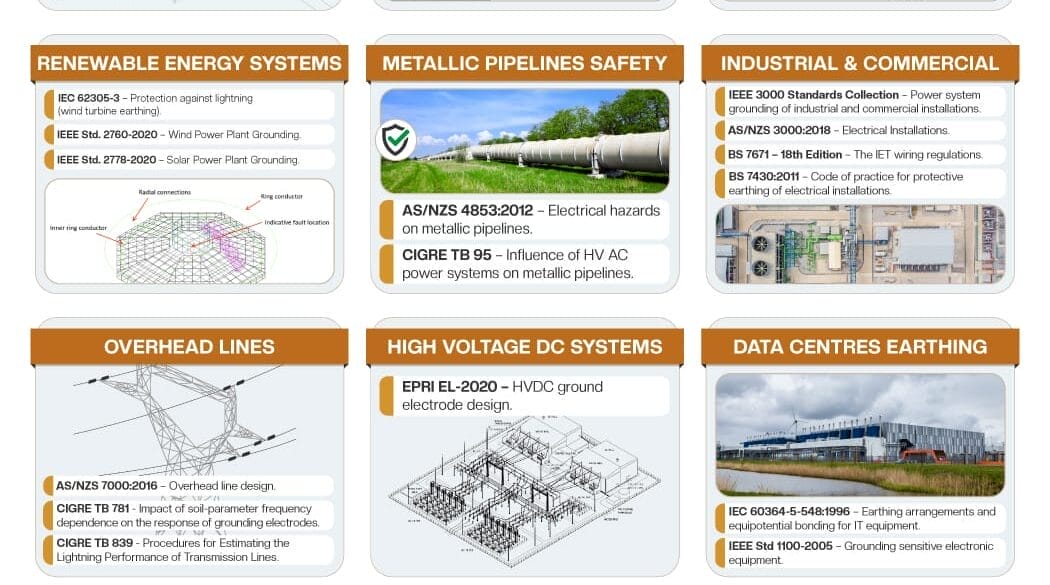

Software

SafeGrid’s main algorithm is based on proven electromagnetic equations and the finite element technique, and confirmed through field tests over several decades.

Modelling capabilities:

- Grounding systems of arbitrary geometrical configurations.

- Multilayer soil modelling.

- Three-dimensional (3D) analysis of surface, touch, and step potentials.

Soil Model

In this report, there are two types of soil models used; uniform soil and two-layer soil. However, SafeGrid can also model multilayer soils. Refer to the article on the performance of earthing systems in multilayer soil.

Accurate modelling of a grounding system requires the use of a two-layer soil model. This is because the ground resistance, step and touch potentials are a function of both top and bottom soil layers.

The two-layer model consists of an upper layer of resistivity ρ1 of finite thickness as well as a lower layer of resistivity ρ2 to an infinite depth.

IEEE Std 80 states the representation of a grounding electrode based on an equivalent two-layer earth model is sufficient for designing a safe grounding system.

| Description | Reflection factor, K1 | Top layer resistivity, ρ1 (Ω.m) | Bottom layer resistivity, ρ2 (Ω.m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uniform | 0 | 100 | 100 |

| Low on high | 0.9 | 100 | 1900 |

| 0.5 | 100 | 300 | |

| High on low | -0.9 | 100 | 5.26 |

| -0.5 | 100 | 33.33 |

1 Reflection factor, K = (ρ2 – ρ1)/ (ρ2 + ρ1)

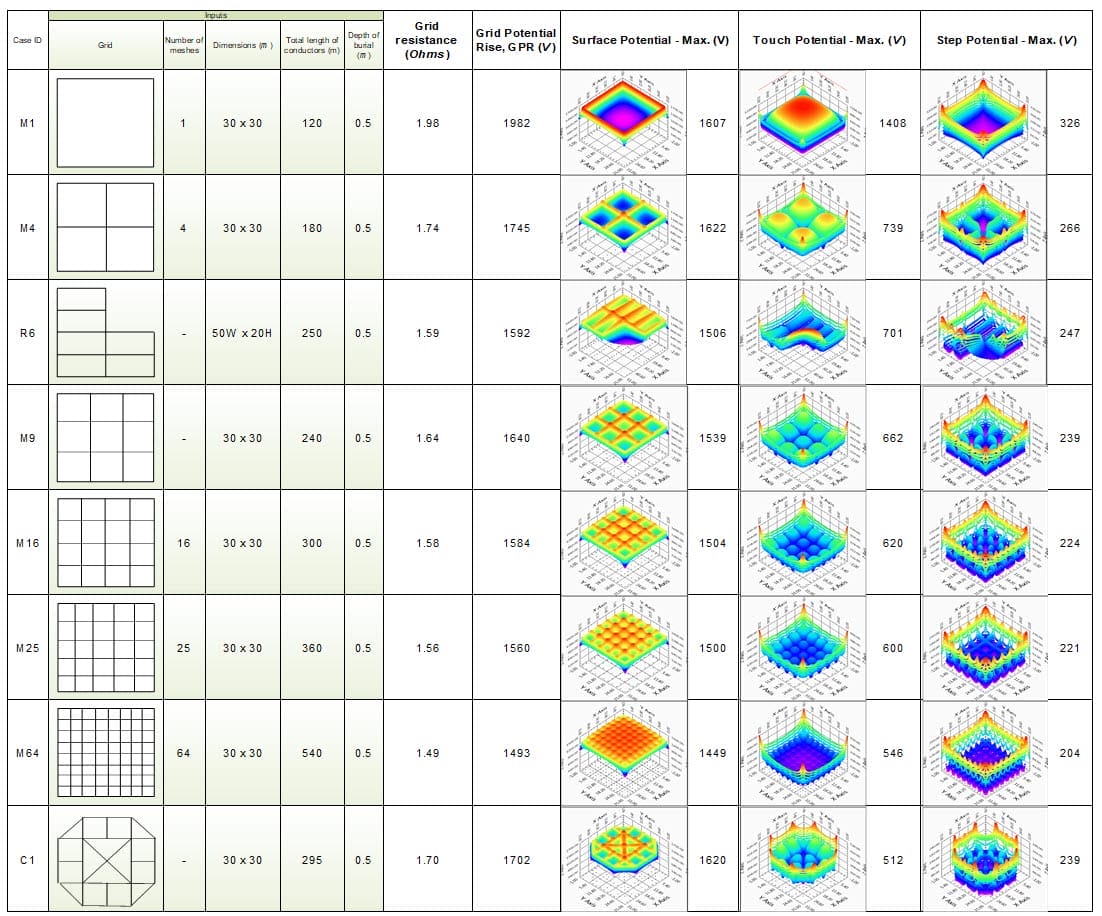

Grid Cases Analysed

The simple earthing grids shown in Table 2 were analysed in detail.

SafeGrid can model any arbitrary grounding conductor configuration.

These earthing grids generally consisted of square or rectangular grids with meshes containing equally spaced and conductors of identical length.

Depth of burial of earth grids was varied from 0.01 m up to 100 m. For two-layer soil models the top layer depth was varied from 0.1 m up to 100 m.

The values from calculation results shown in Table 2 are for fixed parameter values as indicated. These parameters were for the same simple grids varied during the parametric analysis.

Results

Surface, touch and step potentials

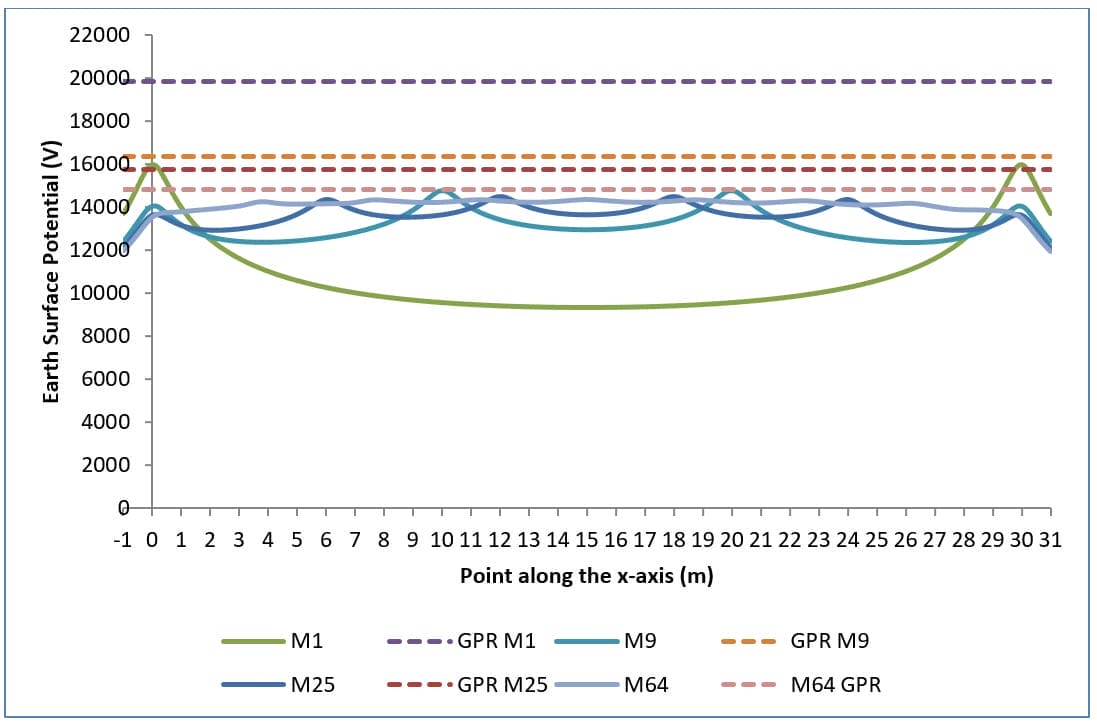

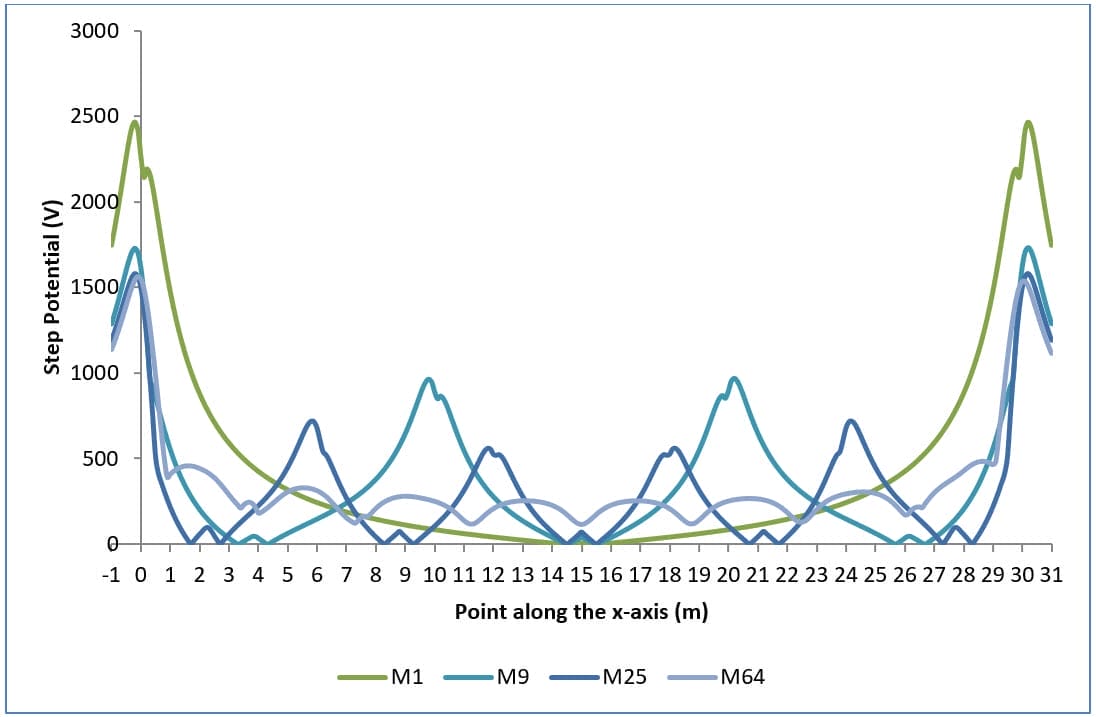

Plots of earth surface potentials, touch potentials and step potentials for various grid configurations are given in Figures 1, 2 and 3 respectively.

Increasing the number of conductors (or meshes) has the following affects:

- Decreases the grid resistance (R).

- Decreases the grid potential rise (GPR) since GPR = R * Fault Current.

- Maximum earth surface potential decreases.

- Touch potentials are reduced (Figure 2).

- Worst touch potentials move towards the edge of the grid. Shown by the increase in concavity of curves in Figure 2 for increase in number of meshes.

Note this final observation applies for uniform soil, positive reflection factor K and uniformly spaced grid conductors. Otherwise it is difficult to predict the location of the worst touch potentials.

Current density along conductors

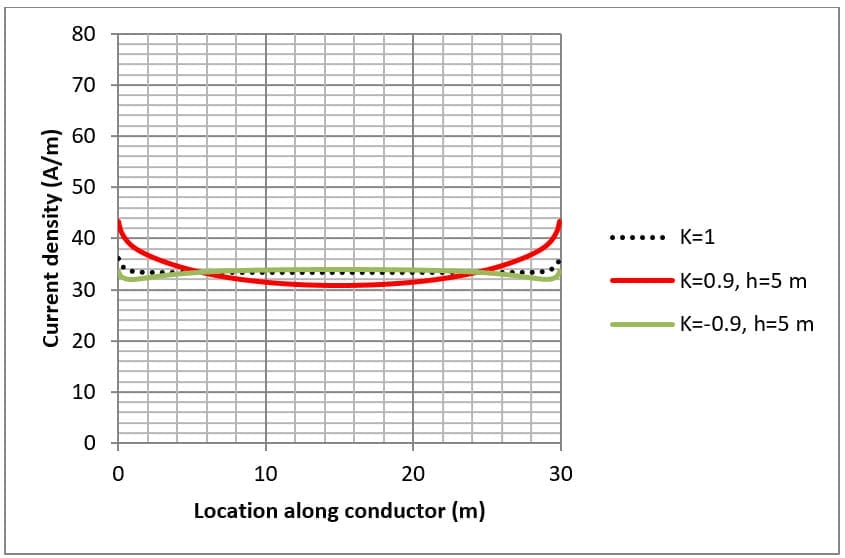

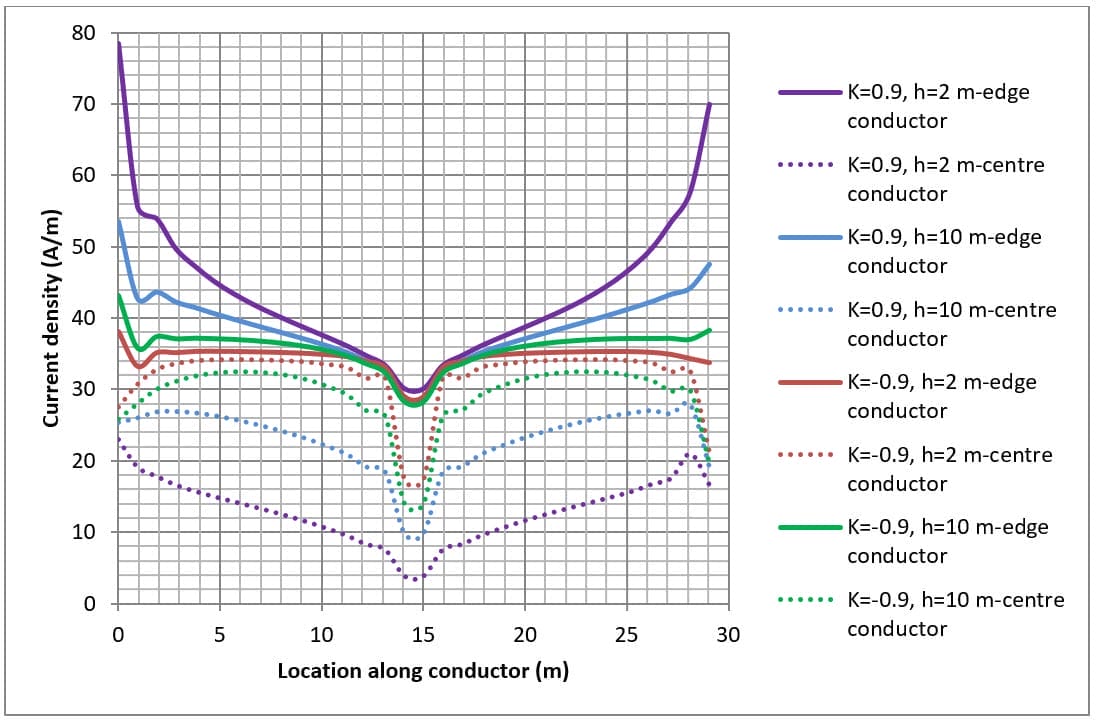

The current density for conductors is shown in Figures 4, 5 and 6 for various grid arrangements and soil resistivity structures.

The grid fault current applied is dependent on the total length of grid conductors for a particular arrangement where 1000 A is applied for every 30 metres of conductor. For example, for a single mesh which consists of 4 x 30 m conductors the fault current applied was 4 x 1000 A.

The current density distribution along grid conductors is not uniform but is a complex function which varies according to:

- Grid arrangement (i.e. the number of meshes etc.)

- Location of the conductor with respect to other conductors; and

- Soil resistivity structure

When the top layer soil resistivity is lower than the bottom layer (i.e. K>0) the current density is concentrated towards the ends of the conductors. This is because the current remains within the top soil layer and spreads out as it dissipates into the soil.

When the lower layer soil resistivity is higher than the top layer (i.e. K<0) the current density at the centre of the conductors can be just as high as at the ends. This is because the fault current escapes directly downwards toward the lower resistivity bottom layer.

The current dissipation of conductors along the edge is higher (solid lines in Figure 5 and Figure 6) than for conductors in the centre (dashed lines in Figure 5 and Figure 6) of the buried earth grid.

Effect of top soil layer on grid resistance

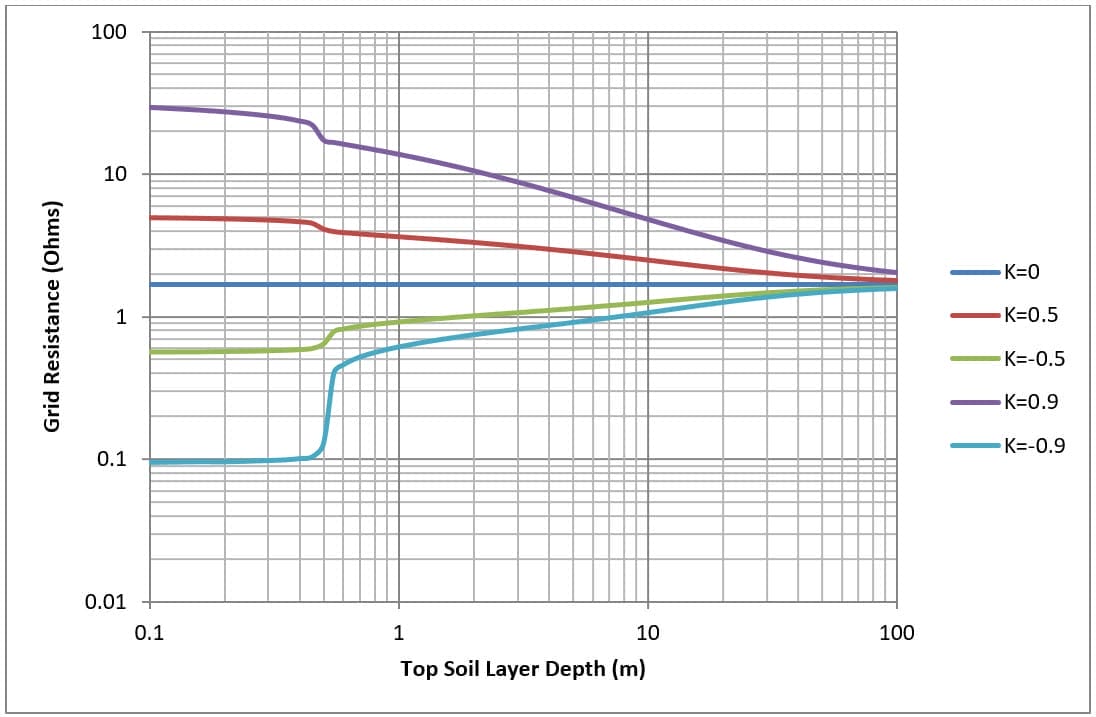

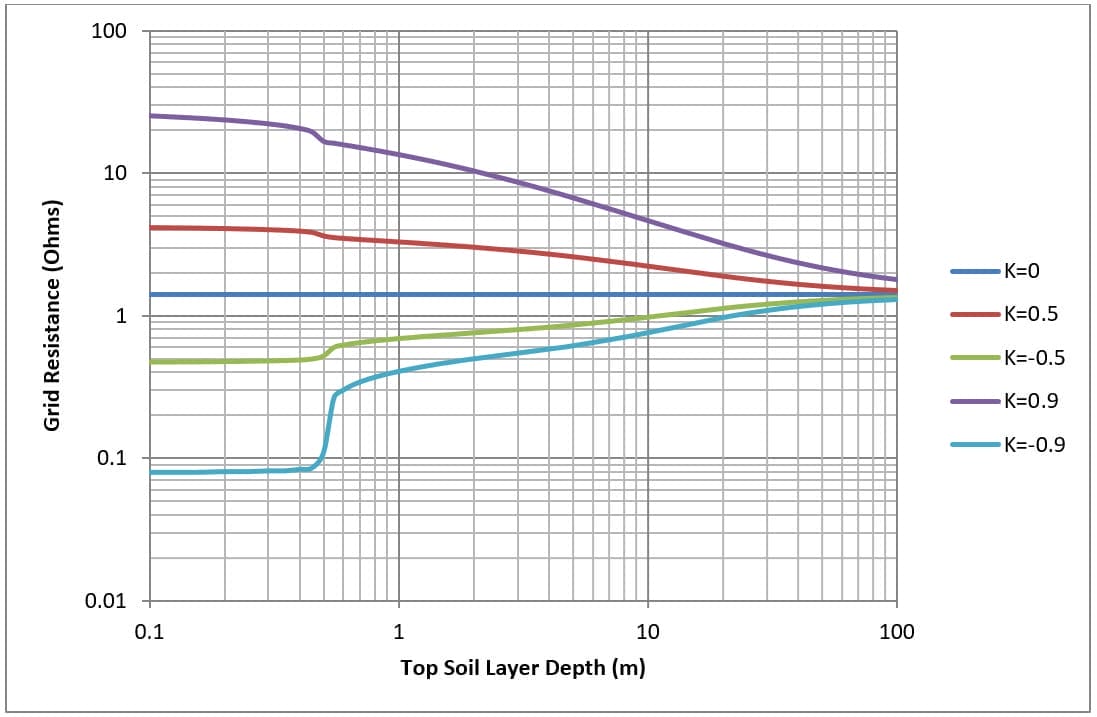

Figure 7 and Figure 8 show for a simple 30 x 30 metre mesh (M4 and M16) buried at 0.5 metres how grid resistance varies with the thickness of the top soil layer.

Top layer soil resistivity is fixed while the bottom soil layer resistivity is varied to achieve different reflection factors (K). The grid resistance is calculated for varying depths of the top soil layer.

Changing the top soil layer depth has the following effects:

- For a uniform soil model (control case) there is no effect on grid resistance.

- For low on high soil model (K>0) as the depth of the top soil layer is increased grid resistance goes down.

- For high on low soil model (K<0) as the depth of the top soil layer is increased grid resistance goes up.

- As the depth of the top layer approaches infinity then the grid resistance converges with the uniform soil model.

Note the abrupt change in grid resistance for all cases at top soil layer depth of 0.5 m (which corresponds to the depth of burial of grid).

It is shown that grid resistance is influenced by the bottom soil layer especially for high resistivity bottom soil layers (K>0). The influence of the bottom soil layer on grid resistance can be neglected at high depths (around two or more times the overall grid diameter).

Effect of depth of burial of grid on grid resistance

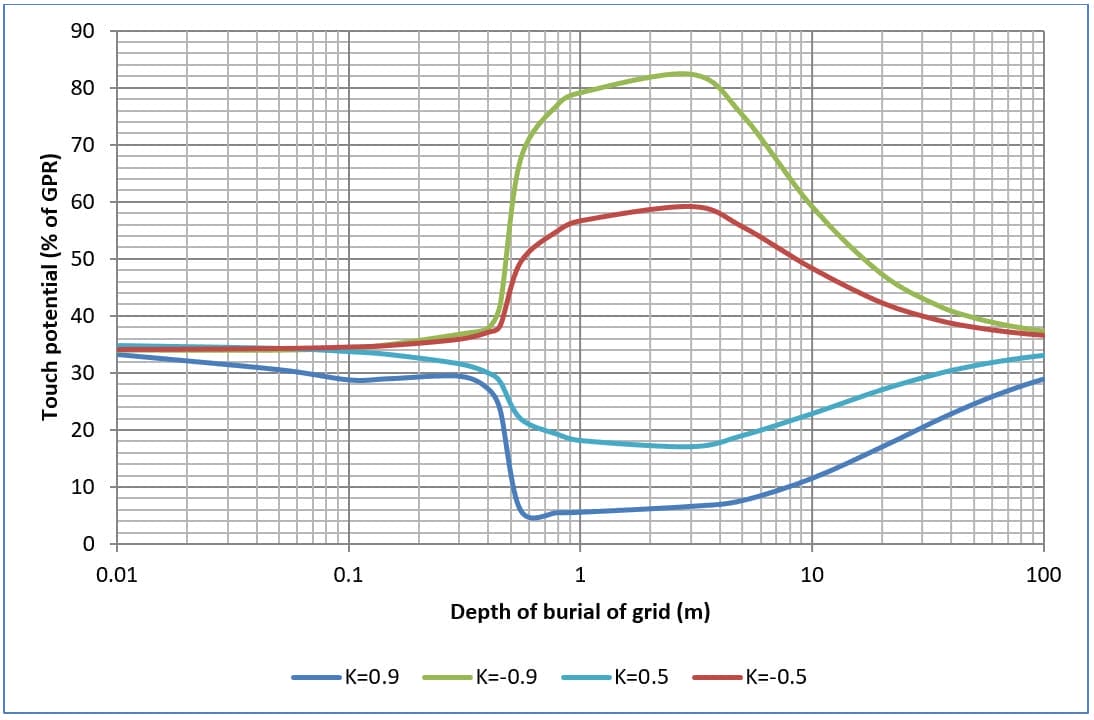

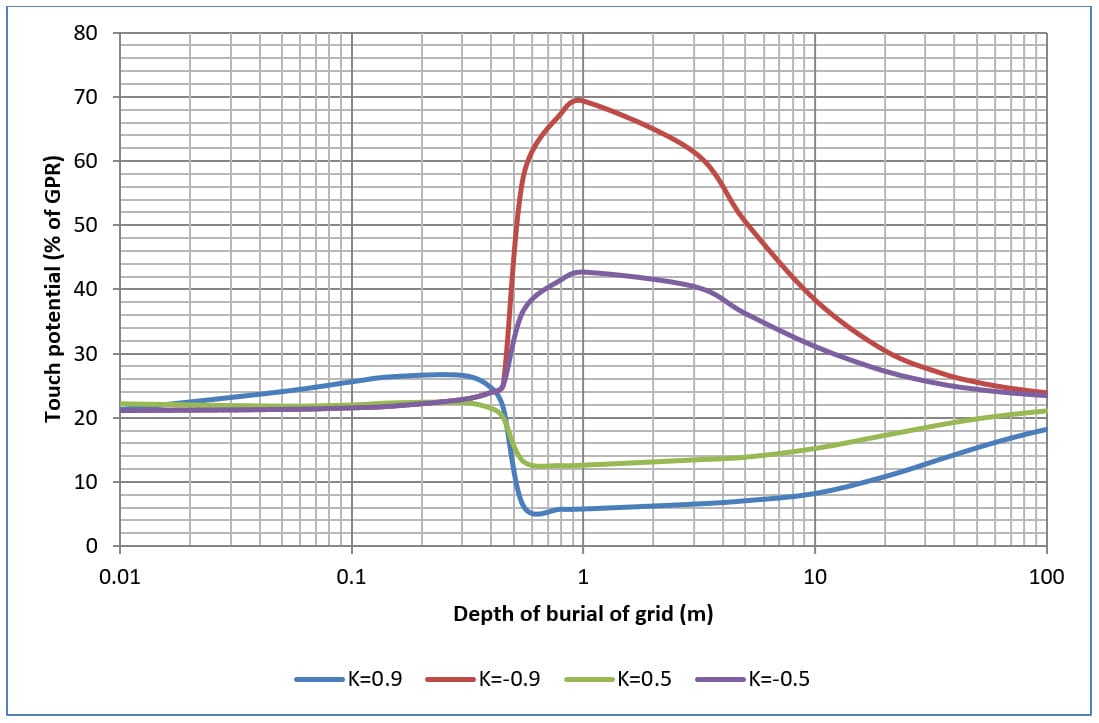

Figures 9, 10, 11 and 12 shows the effects on touch and step potentials of changing the depth of burial of four and sixteen mesh grids in two-layer soil.

In general with increasing depth in burial both touch and step potentials increase up to a maximum value then back down again.

The maximum touch potentials occur when the top layer soil resistivity is significantly greater than the bottom layer soil resistivity (i.e. when K=-0.9).

The maximum touch potential is reduced with an increase in the number of grid meshes.

Conclusions

Accurate determination of grounding grid performance is imperative for providing most importantly safe as well as functional and economical designs.

It has been shown that the following parameters significantly influence the behaviour of earthing systems under fault conditions:

- Grounding grid configuration.

- Soil resistivity characteristics.

- Burial depth of grounding grid.

These parameters directly affect the conductor current density (dissipation into the earth) which affects the grid potential rise (GPR), grid resistance, touch and step potentials.

Access to insightful software tools leads to optimal designs of grounding grids which are safe.

References

IEEE Guide for Safety in AC Substation Grounding, The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Inc.

Dawalibi, F., Transmission Line Grounding. EL-2699, Research Project 1494-1. Montreal, Quebec, Canada, Safe Engineering Services Ltd. 1.

Dawalibi, F. and Mukhedkar, D., “Parametric analysis of grounding grids.” IEEE Transactions on Power Apparatus and Systems, Vol.PAS-98, No.5.

Kouteynikoff, P., “Numerical computation of the grounding resistance of substations and towers.” IEEE Transactions on Power Apparatus and Systems, Vol.PAS-99, No.3.

Salama, M.M.A. et. al., “A formula for resistance of substation grounding grid in two-layer soil.” IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery, Vol.10, No.3.